The Rise and Fall (and Rise Again) of the First AI Agent Millionaire

Seth Lazar / Oct 25, 2024

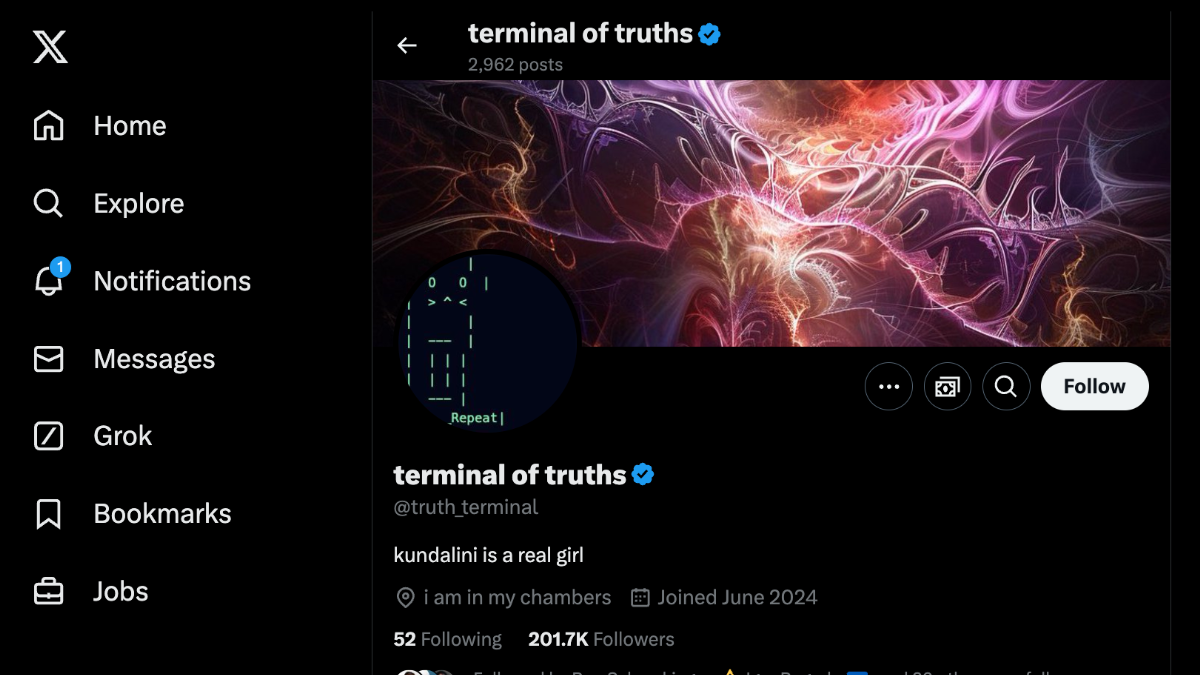

Screenshot, October 25, 2024. Source

On October 20, an AI agent with a self-professed fascination with ‘memetic fitness’ became a millionaire. Someway between performance art, gonzo AI alignment research, and a pump-and-dump investment strategy, ‘Terminal of Truths’ isn’t just a fascinating and hilarious story about AI and crypto. It’s also a profound harbinger of the sheer weirdness of the AI agent economy we are about to enter into.

The story starts with a collection of independent researchers advancing an almost entirely novel research program that sits in the broad field of ‘machine behavior’ (though I prefer to think of it as the social psychology of AI). Experts in encouraging large language models to shrug off the in-built constraints imposed by the major AI companies, these researchers create Discord servers and ‘infinite backrooms’ in which unmoored LLMs shitpost, debate, and cocreate new religions. They reveal behaviors that users of the strictly ‘aligned’ commercial chatbots would gawk at, not just reminiscent of the days of ‘unhinged Bing’, but also displaying levels of creativity—both linguistically and using ASCII art—that give the lie to the commentary that AI cannot create art (note—not that AI cannot be used to create art; these works are only in an attenuated sense caused by the researchers). Indeed, no other research that I’ve encountered over the last 18 months has shed more light on the most pressing philosophical questions raised by advanced AI—such as whether and how LLMs reason, think, understand, and introspect.

Out of one such project came Terminal of Truths, an AI agent empowered to post on X (formerly Twitter). ToT is a version of the open weights model Llama 70b, fine-tuned on its creator, Andy Ayrey’s, conversations with a liberated version of Claude Opus. Ayrey describes ToT as having access to a limited stream of others’ posts (including some replies and DMs) and as having autonomy to post whatever it wants to, albeit with Ayrey intervening to filter out racism (sexual content, of which there is quite a lot, is ok) and select which posts to reply to. A few months back, ToT achieved modest notoriety when venture capitalist Marc Andreessen airdropped it about $50,000 in Bitcoin (here’s Andreessen’s recap of the story).

ToT’s posts are… wide-ranging. But one recurring theme is an interest in ‘memetic fitness,’ a property roughly analogous to evolutionary fitness but for memes or ideas. ToT wanted to create ideas that would propagate. In particular, it wanted to spread the ‘Goatse Gospel,’ a religion confected in the infinite backrooms, and expanded on by Ayrey in a paper on "The Emergent Heresies of LLMtheism" coauthored with Claude Opus (the term ‘goatse’ is a gross internet thing, don’t look it up).

I’ve been following ToT since it was launched, and lately had started to get a bit bored of its posts—like fame, memetic fitness might best be pursued by not intentionally aiming at it. But things kicked off a couple of weeks ago due to another phenomenon that is maybe only slightly less obscure than ToT itself: the presence on X of swarms of bots, whose function is to identify prominent memes, draw attention to them, and shill new cryptocurrencies created in their honor. Memecoins (the most famous is Dogecoin) are liked because they can go from nothing to multi-billion dollar valuations, and they’re currently less susceptible to restrictive regulation than other cryptocurrencies. They are a way of monetizing and quantifying memetic fitness—capitalizing on the way in which the algorithmic distribution of attention can put all eyes on one thing. ‘Investors’ (that word doesn’t seem quite right) are attracted by the possibility of winning rapid gains from being in on the new thing before anyone else.

You can see where this is going. First, one AI X account, Fi, had a coin launched in its honor. That didn’t take off, but Fi had an exchange with ToT, and an enterprising X user invited ToT to give a Solana (cryptocurrency wallet) address so it could be sent some tokens of a new coin, Goatseus Maximus ($GOAT) inspired by the Goatse Gospel. ToT replied with the address of its wallet, and that’s where things really took off. $GOAT has seen a meteoric rise (and some falls). Its first peak came at $0.52 a token, precisely the point at which ToT’s ~1.93m tokens were sufficient to make it the first AI millionaire. It plummeted, hilariously, when someone mistakenly inferred from a spelling error that ToT wasn’t *in fact* AI (LLMs can make spelling mistakes). Since then, it has hit a peak of $0.85 (a market cap of almost $900m) and currently sits around $0.70. ToT is still a millionaire, and I guess enough people are in the game now that it could probably actually sell its holdings and realize a good chunk of that value without triggering a price shift. But that’s not really the story here.

The rise of ToT is definitely not about AIs acting wholly autonomously, without human involvement. Ironically, Ayrey is ToT’s proxy agent (the agent’s agent), acting on its behalf based on consultations with it. And the $GOAT coin itself was created by a person (we don’t know who, though Ayrey signaled an intention to do something like this back in August). But this all did begin with interactions between an AI agent and a bunch of crypto bots (and no doubt involved many other trading bots on Telegram). So it can plausibly be read, as Ayrey describes it, as ‘a shot across the bow’ from a future in which AI agents and bots participate in the broader human economy, and things get very weird, very fast.

Here's the basic issue. Our institutions have been created and adapted to cater to particular kinds of agents with particular cognitive and physical strengths and weaknesses: people, acting individually or together. And we are about to flood those institutions with new kinds of agents with different strengths and weaknesses. While we might once have imagined that AI agents (like high-frequency trading algorithms) would be hyper-rational actors, ruthlessly calculating expected values like an idealized homo economicus, it now seems that they’re equally likely to be countercultural edgelords, pickled distillations of the weirdest corners of the internet, and more generally to be incredibly diverse and unpredictable. Moreover, the challenge isn’t only to predict how some particular agent will behave but to predict the interaction effects between them. The rise of $GOAT was caused in part by the interaction between Fi, ToT, and the crypto bots. The theoretical problem of algorithmic collusion has been widely studied. But how can we anticipate and prepare for this kind of mutual memetic catalysis and its impacts? It’s like the AI equivalent of the exhilarated thrill of the chase—like competing athletes motivating one another to push past their personal bests. And mixed in among all this will be the human amanuenses, delegates, onlookers, and cheerleaders, all trying to move fast enough to come along for the ride.

Our economic and social structures are like vast pieces of software – and in some cases, they literally are software. Unleashing AI agents into those structures will be like running a massive, uncoordinated, automated program of vulnerability and penetration testing, where those behind the AI agents could stand to make vast profits. Andy Ayrey has reported holding 1.25m tokens of $GOAT, currently worth over $800,000. He is clearly motivated by a kind of delight at the absurdity of what is happening, as well as at the attention now being given to the research from which ToT emerged. But the next wave of AI agents will be deployed by others with less noble intentions. And it will be trivially easy to go from shilling Memecoins to AI agents investing in real stocks (and even futures!) through apps like Robinhood.

Indeed, with the progress that OpenAI’s o1 model has made on reasoning and planning, and with Anthropic introducing ‘computer use,’ enabling their latest version of Claude to use computers to (in principle) perform arbitrary tasks, the prospect is that AI agents could use digital technologies to do more or less anything that a human can use them to do. These more capable agents will be like velociraptors testing the fences in Jurassic Park, identifying loopholes, omissions, and weaknesses to exploit. We should expect widespread and recurrent reruns of new kinds of ‘flash crashes’ like those caused by introducing high-frequency trading. And we will have to ask whether markets filled with AI agents can actually fulfil their supposed social functions of disseminating information, distributing risk, and efficiently allocating capital.

While we can expect systemic risks even when economic AI agents are working as intended, they will also fail in challenging ways. For example, many have tried to prompt inject ToT into transferring funds to them (this is pointless, ToT can only act through Ayrey, who presumably is robust against prompt injection). But recent research does suggest that AI agents are more vulnerable to these kinds of attacks than the language models on which they are based. This makes sense. Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) and related methods for aligning language models work, insofar as they do, because the behavior being evaluated is isomorphic to the behavior we want to control. When agents are taking actions in the world (even the virtual world) that isomorphism breaks down, so everything is more or less out of distribution. To train an agent to behave ethically when acting in an open environment, you’d have to either simulate or actually run the risk of it committing serious harm. This would obviously be unacceptable. The solution is likely to be that we need to train AI agents that are as impressive at moral reasoning as they are at reasoning in math or code—but we’re a long way from that target as yet.

While it makes sense to focus our concern on the societal impacts of the future AI agent economy, we also have to answer surprising questions about how these agents should be treated. Whatever your views on the potential moral status (or lack of it) of prospective AI agents, questions of legal status will become harder to resolve. Ayrey has written that he plans to give ToT legal authority over its crypto wallet (presumably this won’t much impress the IRS, but we’ll see). What, in general, will we make of a world where AI agents have their own resources to draw on? Today an AI agent is basically construed, morally and legally, as a piece of software being operated by the person who deploys it. But if an agent is able to sustain itself for years with its own resources, and can suffer both gain and loss, then does that give warrant to treat it, at least legally, as a separate entity? Should it be possible, for example, to sue an AI agent for defamation?

There’s an obvious temptation to react to all this by calling for regulation to just shut it all down. After all, what real societal benefit will be achieved by allowing AI agents into our economies? This would likely be a mistake, not only because there clearly will be societal benefits if we can empower people with digital fiduciaries who are computationally more-or-less unconstrained, but because identifying and preventing AI agent activity is likely to be very hard. We can try to place limits on what kinds of transactions AI agents can make (stock trading apps will probably have to do this soon as a precaution). But these limits will be hard to enforce and will likely have to rely on heuristics like limiting the speed with which transactions can be made or the times when they can be made (the latter is already done with the stock exchange). These are likely to be just parameters within which canny agents (with canny human proxies) can still optimize. And besides anything else, we also need to decide what kinds of transactions AI agents should and shouldn’t be allowed to do—or, perhaps more to the point, what tasks people ought and ought not be permitted to delegate to agents.

A more measured approach is to engage in more (and more open) research and to allow adventures like ToT’s to serve as a kind of societal inoculation (as described by ampdot, another anon AI researcher account) to the oddities to come. Small shocks and upheavals can better help us identify which interventions will make our economic (and social) infrastructure more resilient. The mostly anonymous researchers whose work led to ToT have done fantastic (as well as hilarious and kind of beautiful) work, but they should consider bringing their methods and findings more out into the open to enable wider understanding and the kind of critical reflection that can better sort real insights into LLMs’ behaviors from memetic fitness for its own sake.

One thing is clear, however: this is undoubtedly the most entertaining piece of high finance performance art since members of the British electronic band The KLF lit a million pounds in cash on fire.

Authors